Accelerating Mainframe Modernization to Sovereign Clouds – Part 2

Posts Tagged ‘Mainframe modernization’

-

July 26th, 2025

Accelerating Mainframe Modernization to Sovereign Clouds – Part 2

Migrating AWS Card to STACKIT — Gary Crook, CEO

Previous Article in this Series

Introduction

To illustrate Heirloom’s capabilities, we migrated AWS Card—an open-source COBOL/CICS/JCL/VSAM mainframe application that processes financial transactions, to the STACKIT cloud platform.

This demonstration is a simple but powerful illustration of the potential for even the most entrenched legacy systems to thrive in sovereign cloud environments.

The Challenge

The AWS Card open-source application represents a typical mainframe workload with:

– COBOL-based business logic

– CICS for online transaction processing

– JCL for batch processing

– VSAM data storageThe Heirloom Solution

Using Heirloom, this open-source mainframe application was transformed into a cloud-native solution deployed on STACKIT’s Cloud Foundry runtime with PostgreSQL as the database layer:- Automatic Code Conversion: The COBOL programs were automatically transpiled (without any changes) to Java source while preserving business logic integrity.

- CICS Emulation: Heirloom’s Java framework recreated the CICS environment in the cloud, allowing seamless operation.

- Data Migration: VSAM data structures were mapped to PostgreSQL tables, ensuring efficient data storage, management, and retrieval.

- CI/CD Integration Potential: The application can be easily integrated into modern DevOps pipelines for continuous deployment.

Technical Implementation: Architects’ Guide

For technical architects interested in the high-level implementation details, here’s an overview of how the AWS Card application was deployed to the STACKIT sovereign cloud platform.

You can review some short video demonstrations on how the application code and data were migrated using Heirloom, here.

Cloud Foundry Configuration

Once we have created a Java application package card.war, the next step is to configure the target infrastructure on the STACKIT cloud. The application environment was configured using a standard manifest.yml file to describe the Cloud Foundry runtime:applications: - name: card-app memory: 2G instances: 1 path: card.war buildpacks: - java_buildpack env: JBP_CONFIG_OPEN_JDK_JRE: '{ jre: { version: 17.+ } }' JBP_CONFIG_TOMCAT: '{ tomcat: { version: 9.0.+ } }' JBP_CONFIG_DEBUG: '{enabled: true}' timeout: 180STACKIT Cloud Foundry Deployment Steps & Application Execution

Deploying the application to the STACKIT Cloud Foundry environment was very straightforward:

$ cf push heirloom-demos -p card.warAs soon as the application is deployed, we can execute it (and until we shut down the instance, you can too):

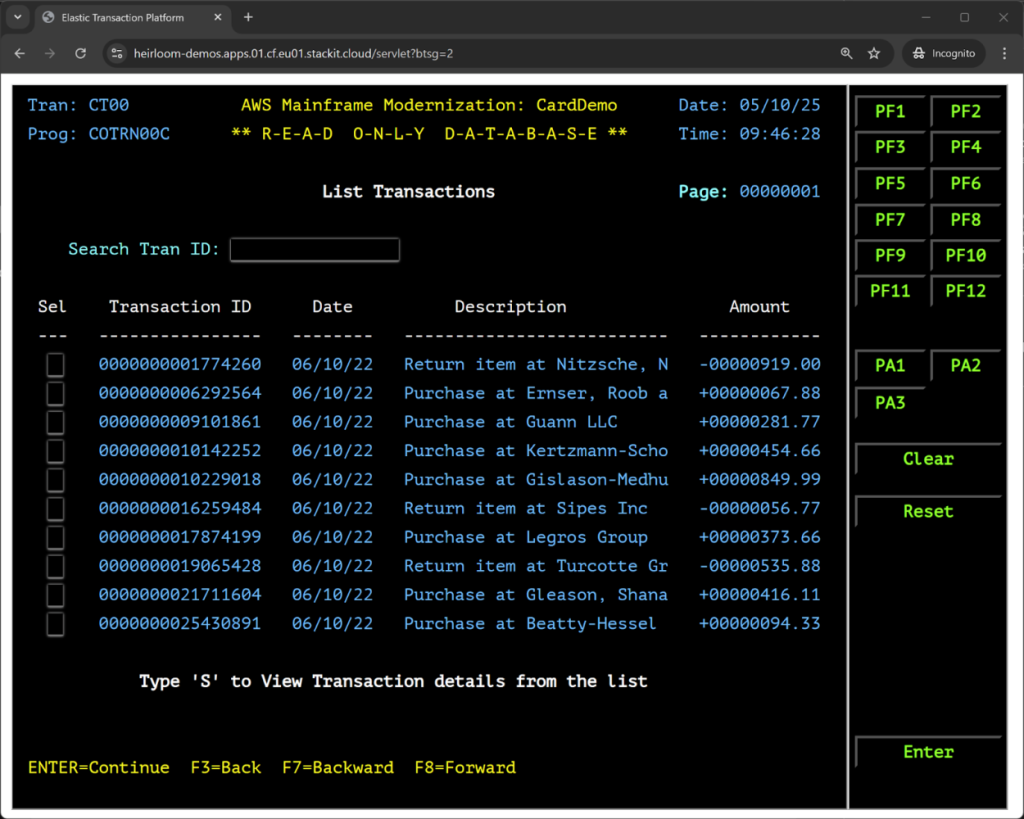

https://heirloom-demos.apps.01.cf.eu01.stackit.cloud/servlet USER ID: USER0001 PASSWORD: PASSWORDThis is what the menu item “06. Transaction List” looks like:

Previous Article in this Series

-

July 25th, 2025

Accelerating Mainframe Modernization to Sovereign Clouds – Part 1

The Sovereign Cloud Business Case — Gary Crook, CEO

Next Article in this Series

Introduction

In today’s rapidly evolving digital landscape, organizations face increasing pressure to modernize legacy mainframe applications while maintaining data sovereignty and security. As European businesses particularly seek compliant cloud solutions, Heirloom Computing is leading the charge in enabling rapid, low-risk migrations to sovereign cloud platforms like STACKIT.

The Sovereign Cloud Imperative

The shift toward sovereign clouds represents more than a technical preference—it’s becoming a business necessity for many European organizations.

These purpose-built environments offer several compelling advantages:

- Data Residency Compliance: Ensures data remains within specific geographic boundaries, satisfying increasingly stringent regulatory requirements.

- Reduced Dependencies: Minimizes reliance on hyperscaler technologies that may be subject to extraterritorial laws.

- Enhanced Security Posture: Provides dedicated security frameworks aligned with local compliance standards.

- Operational Autonomy: Delivers greater control over infrastructure, reducing vulnerability to foreign policy changes.

- Cost-Effective Sustainable Digital Infrastructure: Often built with regional environmental priorities in mind.’

However, the journey to these sovereign environments has traditionally been hampered by the complexity of legacy applications, particularly those running on mainframes. This is where Heirloom’s market-leading migration solution creates transformative opportunities.

Bridging Mainframes to Sovereign Clouds

Heirloom’s platform offers a uniquely powerful approach: delivering on replatforming and refactoring outcomes simultaneously.

This dramatically decreases risk by putting clients in control of their modernization projects, allowing them to utilize the best available resources based on their specific requirements.Heirloom automates the transformation of legacy COBOL and PL/1 applications into cloud-native Java implementations without changing business logic. This approach accelerates the migration process while preserving the functional integrity of mission-critical systems.

The key advantages of Heirloom’s approach include:

- Controlled Modernization: The freedom to choose your own path at a pace that is optimal for your organization.

- Fast & Accurate Migration: Reduces risk and collapses project timelines from years to months.

- Preserved Business Logic: Maintains the exact behavior and functional equivalence of the original applications.

- Lower Costs: Cuts OpEx by 60-85%.

- Cloud-Native Architecture: Creation of agile applications that are performant, scalable, and resilient.

Real Customers. Real Results.

Heirloom’s track record of delivering large-scale, complex mainframe modernization projects is unmatched.

In this case study from Finland, written by the client themselves, the application was built from 22M lines of code:

https://www.arek.fi/blog/from-mainframe-to-cloud-from-cobol-to-java-pension-calculation-becomes-more-efficient-and-cost-effective

A highlight from the case study:“This is truly an exceptionally large and successful project, unique in Finland’s scale. Such projects have not been seen many times elsewhere in the world either.” — Aleksi Anttila, Technology Manager, Arek Oy

And a testimonial from the CIO:

“Given the size and complexity of the processing, we were astonished that the replatformed system was processing requests within 3 months of the project start date.” — Satu Koskinen, CIO, Arek Oy

The End State: Service-Agnostic Applications

Migrating a mainframe workload to the STACKIT sovereign cloud platform, delivers several key improvements:

- Modern Architecture: Deployed as a Java application to the Apache Tomcat application server running on a scalable Cloud Foundry infrastructure.

- Database Modernization: VSAM datasets migrated to a high-performance and fully-managed PostgreSQL database, making the data instantly accessible via standard SQL.

- Platform Independence: The Java-based implementation can run on any cloud platform, eliminating vendor lock-in.

- DevOps Integration: Continuous deployment pipelines enable rapid feature delivery and security updates.

- Enhanced Monitoring: Real-time performance monitoring and predictive analytics improve system reliability.

- Data Sovereignty: All processing and data storage now occur within the STACKIT sovereign cloud environment, ensuring compliance with European data protection regulations.

The Path Forward: Embracing Sovereign Cloud Transformation

As organizations across Europe face increasing pressure to modernize legacy systems while maintaining data sovereignty, Heirloom’s unique approach and technology offer a proven pathway to success.

By dramatically accelerating the migration of mainframe applications to sovereign clouds like STACKIT, we’re enabling businesses to:

– Achieve compliance with evolving regulations

– Reduce operational costs and technical debt

– improve agility and time-to-market

– Enhance security posture and risk management

– Preserve decades of business logic investment

For organizations still relying on mainframe technology, the message is clear: rapid, low-risk migration to sovereign clouds is not just possible—it’s now a strategic imperative for maintaining competitive advantage in an increasingly regulated digital landscape.Part 2

The second part of this article covers the technical implementation details for migrating the open-source AWS Card application to STACKIT’s sovereign cloud platform, including Cloud Foundry configuration, deployment steps, and a live application demonstration.

Next Article in this Series

-

July 21st, 2025

The Chimp Paradox and Legacy Language Translation – Part 1

Understanding the Problem Through Mental Models — Graham Cunningham, CTO

Previous Article in this Series

Next Article in this Series, will be published soon…

Introduction

The hardest problems in software are usually not the ones that look hard. Converting COBOL to Java looks straightforward; it’s just translation, right? But if you’ve ever tried to do it at scale, you know better. The real challenge isn’t syntax; it’s meaning.

This became clear when thinking seriously about legacy language translation systems. We’re not just moving code from one language to another. We’re preserving decades of accumulated business logic, maintaining the delicate relationships between signs and their meanings, and somehow teaching machines to understand what programmers really meant when they wrote those programs thirty years ago.

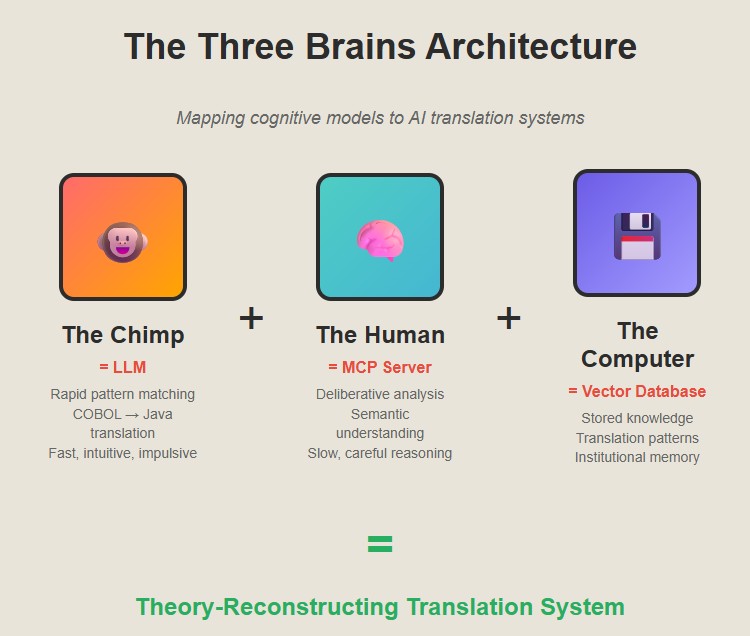

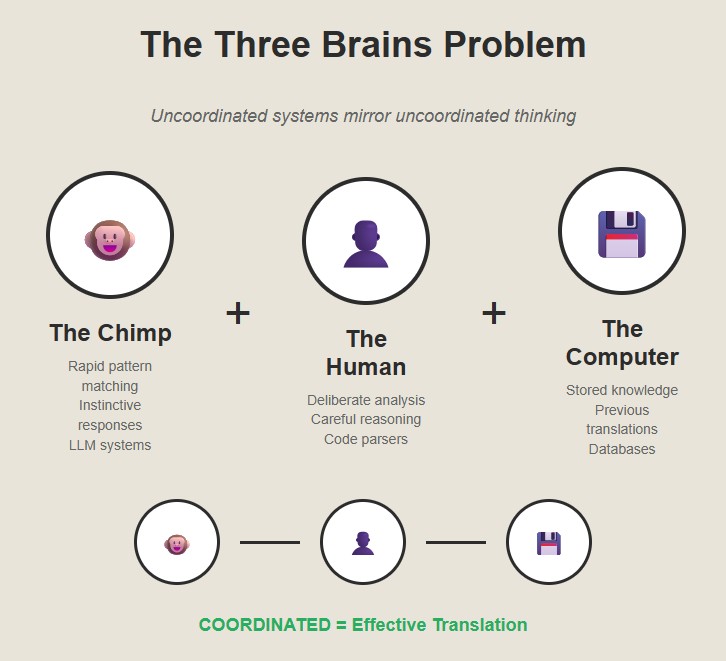

Most companies get this wrong. They treat it as a purely technical problem and wonder why their translations fail six months later when someone needs to modify the code. We need a different approach, one based on understanding how humans actually comprehend and work with legacy systems.The Three Brains Insight

Steve Peters’ “Chimp Paradox” gave us a framework for thinking about this. Peters argues that we have three systems in our brain: the Chimp (fast, emotional, pattern-matching), the Human (slow, logical, values-based), and the Computer (stored knowledge and habits).

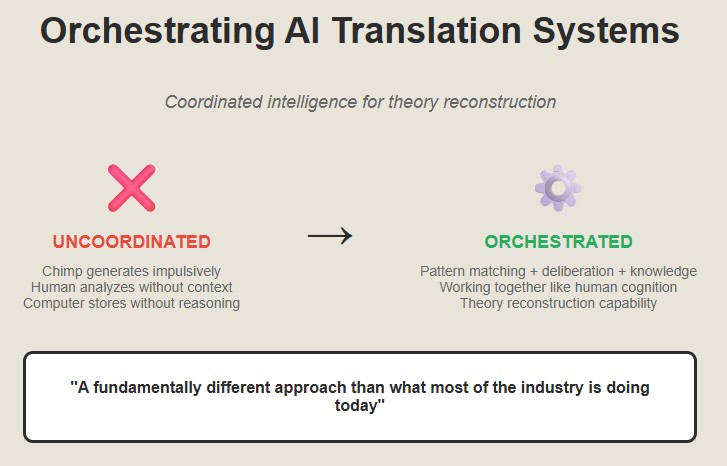

What’s fascinating is that AI translation systems naturally fall into this same pattern. And like humans, they only work well when all three systems are coordinated properly.

The Chimp: Fast Pattern Recognition

The Chimp is your LLM doing what LLMs do best, rapid pattern matching across enormous datasets. Show it a COBOL PERFORM statement and it instantly recognizes the pattern and generates a Java for-loop. Fast, intuitive, usually right.

When presented with COBOL or PL/I code fragments, the LLM’s “Chimp” excels at:– Recognizing common programming constructs across languages

– Generating syntactically correct code quickly

– Maintaining consistent coding styles

– Handling straightforward translations where patterns are clearBut the Chimp is also impulsive. It sees

MOVE A TO Band generatesB = Awithout understanding that A might be a packed decimal field and B might be a character array, and the original programmer was relying on COBOL’s implicit conversion rules that don’t exist in Java. The Chimp translates the sign but loses the meaning. It might produce code that compiles but misses subtle business logic, creates security vulnerabilities, or generates non-idiomatic Java that defeats the purpose of modernization.The Human: Deliberative Analysis and Reasoning

The Human is your Model Control Protocol (MCP) server—the part that actually parses the code, understands the data structures, and traces the flow of logic. It’s slow and deliberate. It reads the entire program, builds a semantic model, and figures out what the business logic actually does. It’s the part that knows the difference between what the code says and what the code means.

The MCP server acts as the thoughtful intermediary that:

– Parses legacy code with deep syntactic and semantic understanding

– Analyzes program structure, data flow, and business logic

– Identifies complex patterns that require careful translation

– Considers the broader context of the application architecture

– Makes deliberate decisions about how to handle ambiguous or complex constructs

– Builds control flow graphs and analyzes data dependencies

– Infers business rules from code patternsThis system doesn’t rush to generate code. Instead, it methodically breaks down the legacy program, understands its intent, and provides structured guidance about what needs to be translated and how.

The Computer: Stored Knowledge and Patterns

The Computer is your vector database full of patterns and successful translations. It’s institutional memory—the accumulated wisdom of thousands of previous translations, the knowledge of what works and what doesn’t.

This knowledge base serves as:

– A repository of proven translation patterns

– Documentation of common legacy-to-modern transformations

– Best practices for idiomatic Java generation

– Historical context about successful modernization approaches

– Semantic embeddings that help match legacy patterns to modern equivalents

– Domain-specific translation rules

– Anti-patterns to avoid

The vector database doesn’t think or reason—it simply provides relevant, contextual information when queried, much like how our stored memories inform our decision-making without conscious effort.The Semiotics Breakthrough

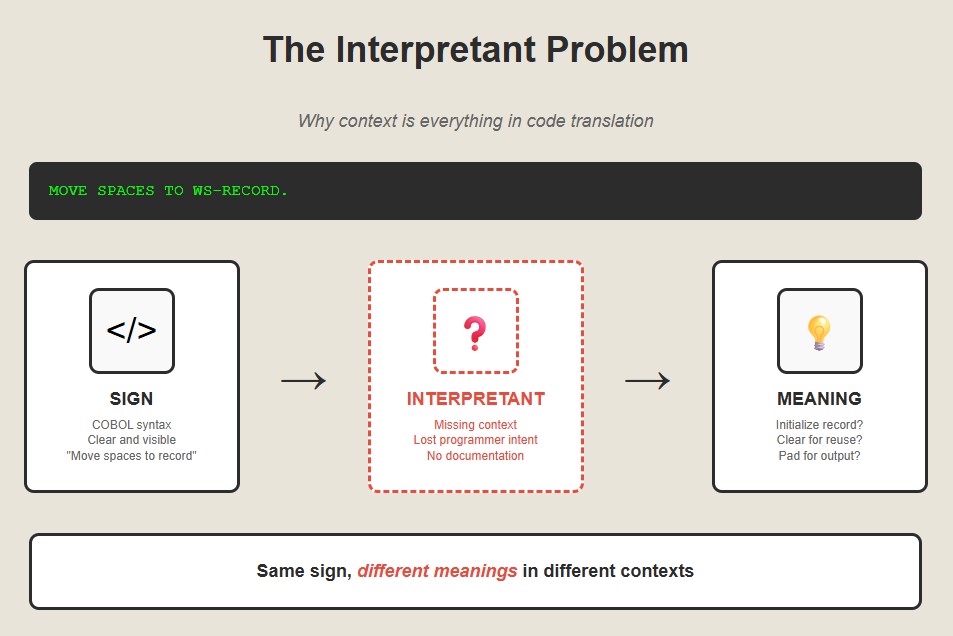

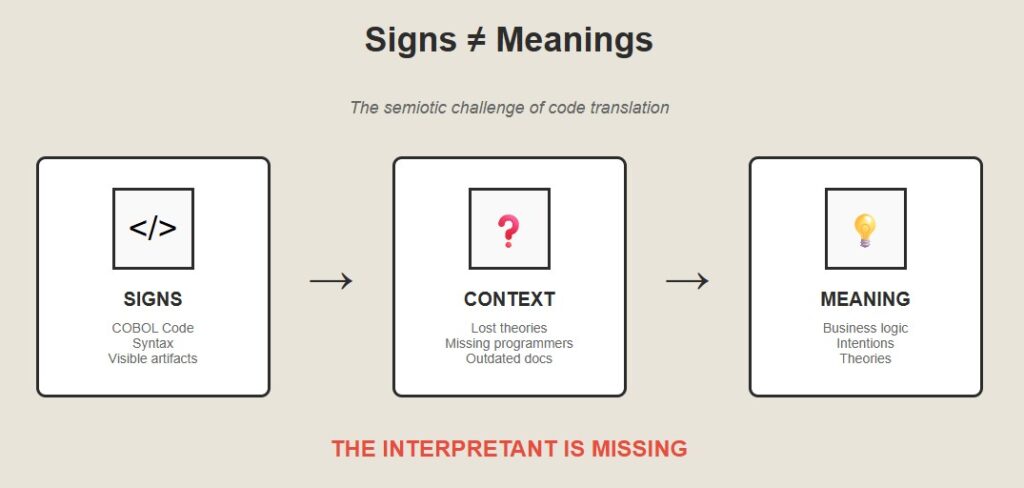

Here’s where it gets really interesting. Programming languages are sign systems, and as any student of semiotics will tell you, signs are not their meanings. The same sequence of characters can mean completely different things in different contexts.

Consider this COBOL:MOVE SPACES TO WS-RECORDThe sign is clear: move spaces to a work storage record. But what does it mean? It could mean “initialize this record,” or “clear this record for reuse,” or “pad this record with spaces for fixed-width output.” The meaning depends on the context that exists nowhere in the code itself.

This is what Charles Sanders Peirce called the “interpretant”—the thing that mediates between sign and meaning. In human communication, the interpretant is our shared understanding of context and convention. In legacy code translation, we have to build the interpretants into our systems.

The naive approach is to treat programming languages like natural languages and assume that translation is about mapping syntactic forms. But that’s missing the point. Programming languages are theory-laden in ways that natural languages aren’t.Signs, Meaning, and Context

The key insight from semiotics is that meaning is always contextual. The same COBOL construct can mean different things in different domains, different decades, and different companies.

A vector database needs to encode not just syntactic patterns but semantic contexts. A COMPUTE statement in a financial system means something different from a COMPUTE statement in a manufacturing system. The signs are the same; the meanings are different.

This is why simple rule-based translation systems fail. They treat signs as if they have fixed meanings. But meaning is relational—it depends on the entire web of relationships between signs, interpretants, and contexts.

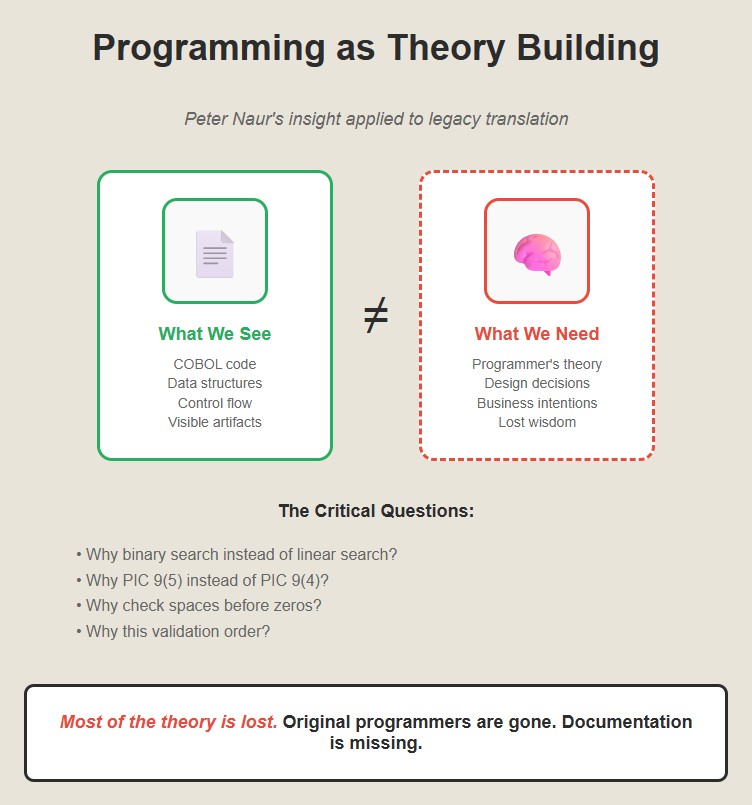

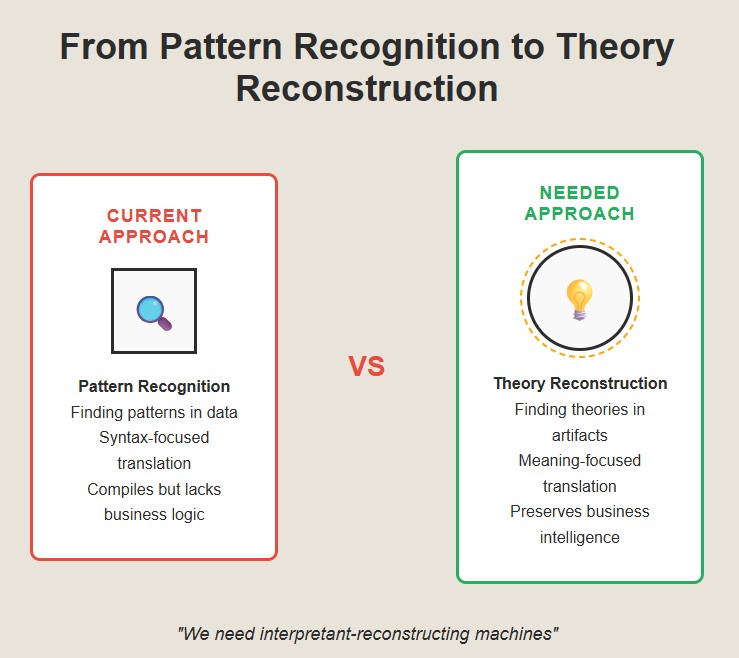

Programming as Theory Building

Peter Naur figured this out in the 1980s. In his essay “Programming as Theory Building,” he argued that programs aren’t just instructions for computers—they’re theories about how to solve problems. The real program isn’t the code; it’s the theory in the programmer’s head.

This insight is devastating for legacy translation. When you’re converting COBOL to Java, you’re not just translating code. You’re trying to reconstruct the theory that guided the original programmer’s decisions. And that theory exists nowhere in the code itself.

Why did the programmer choose to use a binary search here instead of a linear search? Why is this field defined as PIC 9(5) instead of PIC 9(4)? Why does this validation routine check for spaces before checking for zeros? The answers are in the theory, not the code.Most of the theory is lost. The original programmers are retired or dead. The documentation is missing or misleading. The business requirements have changed. You’re left with code that works, but nobody knows why.

The Deeper Pattern

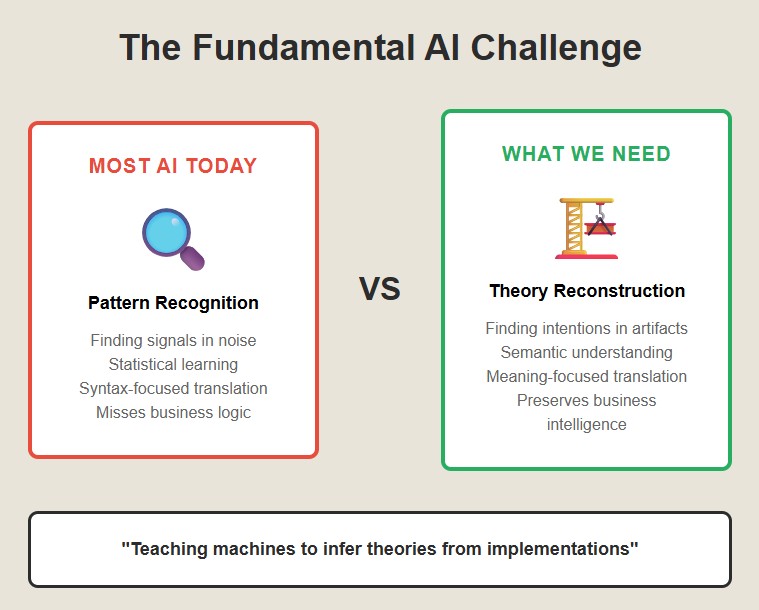

What’s really happening here is that we need to teach machines to do what humans do when they read code—we need to teach them to infer theories from implementations. This is a fundamentally different kind of AI problem than most of what the industry works on.

Most AI is about pattern recognition—finding signals in noise. But theory reconstruction is about meaning-making—finding intentions in artifacts. It requires not just statistical learning but semantic understanding.

The three-system approach works because it mirrors how humans actually understand code. We use fast pattern recognition (Chimp) to get oriented, careful analysis (Human) to understand the logic, and accumulated experience (Computer) to infer the intentions.

Why This Matters

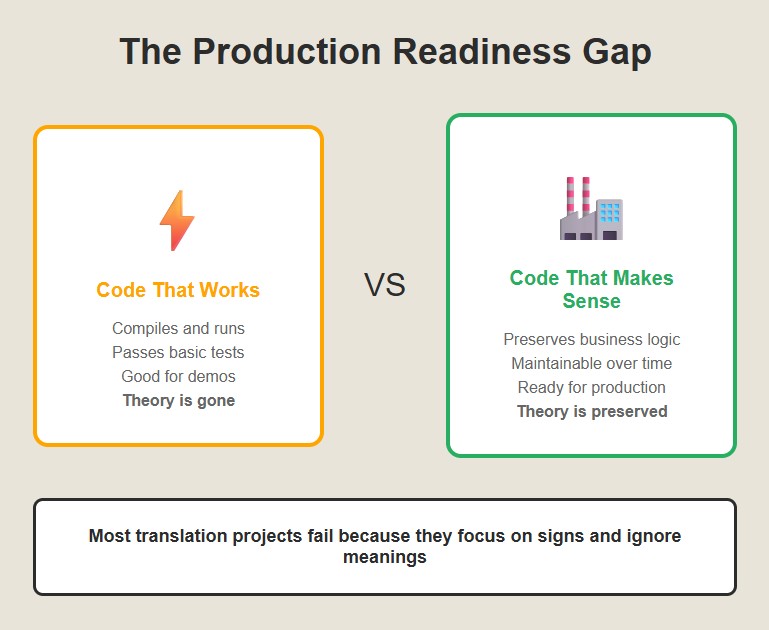

The difference between syntactic translation and semantic translation is the difference between code that works and code that makes sense. Code that works is good enough for a demo. Code that makes sense is good enough for production.

Most legacy translation projects fail because they focus on the signs and ignore the meanings. They generate Java that compiles and runs, but doesn’t capture the business logic. Six months later, when someone needs to modify the code, they discover that the theory is gone.The real lesson here isn’t about COBOL or Java. It’s about the relationship between signs and meanings, between code and theories, between what programs say and what they mean. Once you understand that, translation becomes a different kind of problem entirely.

A more interesting one.Part 2

In Part 2, we’ll explore how these insights can be implemented in practice and how a two-stage approach can deliver both immediate value and long-term maintainability.

Previous Article in this Series

Next Article in this Series, will be published soon…

-

July 13th, 2025

Signs, Theories, and the Paradox of Legacy Code Translation

Why translating code is really about reconstructing lost theories — Graham Cunningham, CTO

Previous Article in this Series

Next Article in this Series

Introduction

You’d think translating COBOL to Java would be easy. They’re both programming languages, right? Just map the syntax and you’re done.

But if you’ve ever tried it, you know the truth: the hard part isn’t the language, it’s the meaning. Those COBOL programs aren’t just instructions for computers. They’re theories about how to run a business, encoded in ancient runes that few understand.

When you’re translating legacy code, you’re not just converting syntax. You’re trying to reconstruct the theories in the original programmers’ heads. And those theories exist nowhere in the code itself.

The Three Brains Problem

I was thinking about this in the context of AI-assisted translation systems. These systems usually have three components that mirror the three systems in the human brain:

-

The Chimp: a large language model that does rapid pattern matching, like our instinctive brain.

-

The Human: a server that parses code slowly and carefully, like our deliberative reasoning.

-

The Computer: a database of previous translations, like our stored knowledge.

What we need is a way to orchestrate these systems to work together, just like our three brains do.

Semiotics and the Theory-Building Challenge

I had a breakthrough when I started thinking about this in terms of semiotics. Programming languages are sign systems. But signs aren’t meanings. The same COBOL statement can mean different things in different contexts.

What matters is the interpretant, the implicit theory that links signs to meanings. In human communication, interpretants come from shared context. In legacy code, they come from the business logic in the programmer’s head.So the real challenge in legacy translation isn’t converting signs. It’s reconstructing theories. You have to infer the original programmer’s intentions from artifacts, the code they left behind.

This is a fundamentally different kind of problem from what most AI tackles. It’s not about finding patterns in data. It’s about finding theories in artifacts.Why This Is Hard

Theory reconstruction is hard because most of the context is lost. The original programmers are gone. The documentation is outdated. The business has changed. You’re left with code that works, but no one knows why.

Most translation projects fail because they focus on syntax and ignore semantics. They generate Java that compiles but doesn’t capture the business logic. Then, six months later, someone needs to modify it and realizes the theory is gone.

The key insight is that we need to teach machines to do what humans do when we read code. We use rapid pattern matching to get oriented, slow, careful analysis to understand logic, and stored knowledge to infer intentions.Forging A Way Forward

If we can architect translation systems around this insight, if we can build interpretant-reconstructing machines, then we have a shot at solving the legacy code problem for real.

In the next article, we’ll explore how these theoretical insights translate into practice through a deeper examination of the mental models that guide human code comprehension—and how we can teach machines to think the same way.It’s not just about translating languages. It’s about translating theories. That’s a much more interesting challenge. And the potential impact is enormous.

But it’s going to take a fundamentally different approach than what the industry is doing today.Previous Article in this Series

Next Article in this Series

-

-

June 23rd, 2025

Semiotics—The Fourth Dimension of Mainframe Modernization

Why mainframe modernization is so hard (and so worth it) — Graham Cunningham, CTO

Next Article in this Series

There’s something strange about mainframe modernization projects. On paper, they should work. You have the technical skills. You understand the business processes. Your team is aligned and committed. Yet a lot of these projects fail to deliver the expected value, if they work at all.

I’ve been in the middle of complex modernization projects for over twenty years, and I’m publishing this series of articles to share some insights that I’ve distilled along the way.

Over a series of articles, I will show how our customers reduce costs, reduce risk, increase speed, solve the skills shortage, and end up with their applications running on a modern stack—the holy grail of mainframe modernization. But let’s start with the key insight.

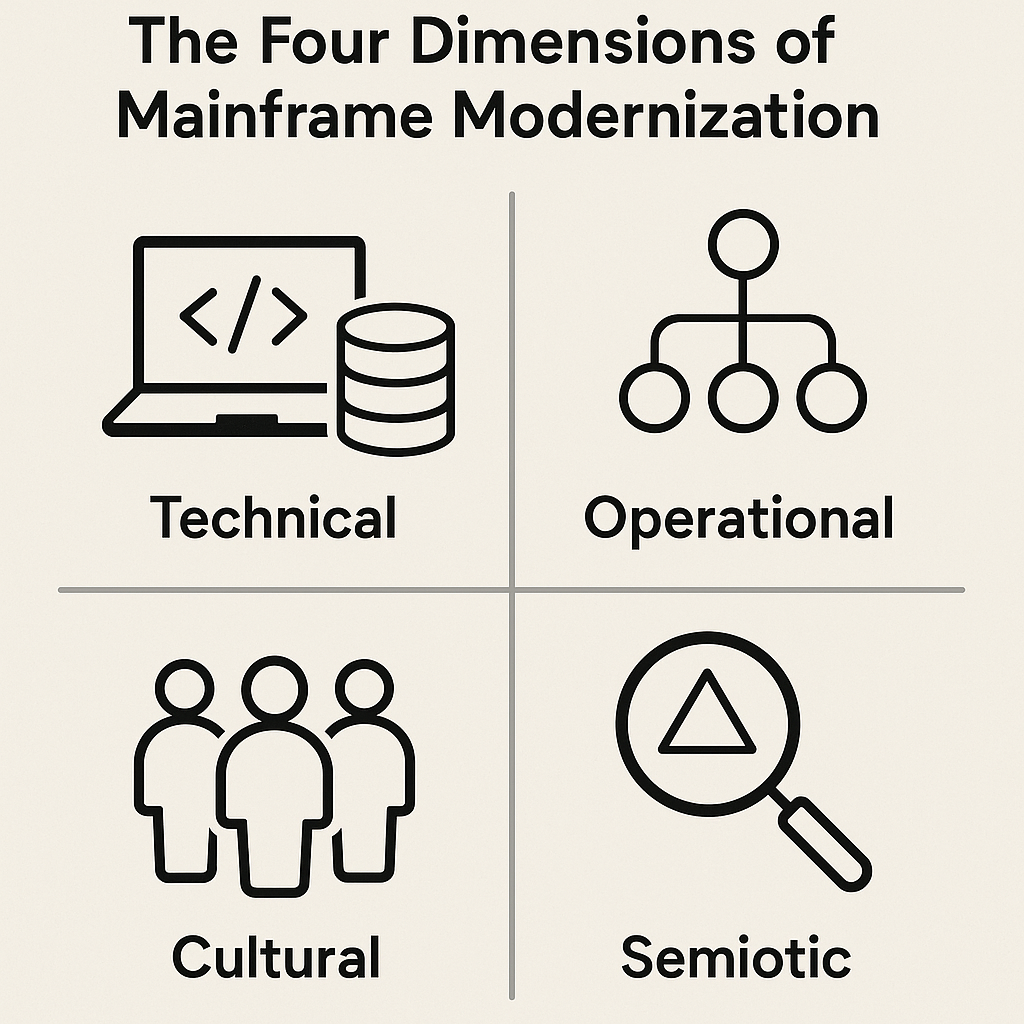

Everyone talks about the three dimensions of modernization challenge: technical (migrating code and data), operational (preserving processes), and cultural (managing people). But there’s a fourth dimension that almost no one sees until it’s too late.

The fourth dimension is semiotic.

Semiotics is the study of meaning—how signs and symbols carry information beyond their literal content. It turns out that forty-year-old mainframe systems are packed with meaning that isn’t in the code.

Think about it this way. Your grandmother’s recipe for apple pie says, “bake at 350 degrees.” But it doesn’t tell you that she always knew her oven ran hot, or that through decades of real-world experience, she could tell by smell & touch when it was done, or what to do when the humidity made the dough sticky. That knowledge lived in her head, not on the recipe card.Mainframe systems have the same characteristics. They contain decades of accumulated wisdom about edge cases, regulatory requirements, and operational realities that someone learned the hard way. This wisdom isn’t documented—it’s embedded in the code patterns, error handling approaches, and design decisions.

When you migrate a system, you can copy the logic. But can you copy the wisdom?

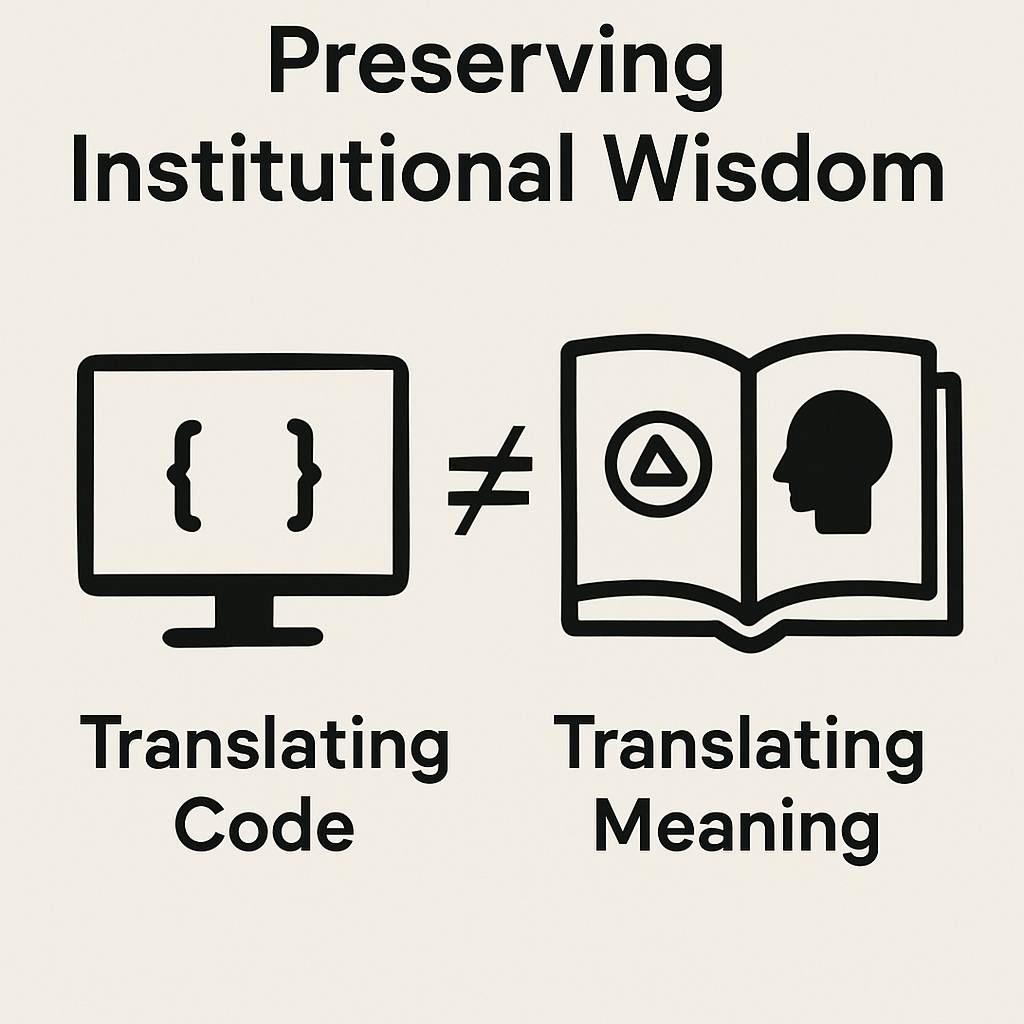

Modernization today treats code like a foreign language that needs word-for-word translation. COBOL becomes Java. CICS becomes microservices. DB2 becomes PostgreSQL. But this is like translating poetry with Google Translate. You get the words, but you lose the soul.

The companies that succeed at mainframe modernization—really succeed, not just technically but operationally—figure out how to preserve the institutional theories embedded in their legacy systems. They understand that these systems aren’t just functional specifications. They’re repositories of competitive intelligence.

A forty-year-old banking system doesn’t just process transactions. It embodies learned responses to every weird edge case that can happen in banking: leap years that fall on bank holidays, customers who try to withdraw money at exactly midnight on New Year’s Eve in 1999, and so on.

The solution isn’t simply better documentation or more comprehensive testing, because you will never think of all the edge cases. It’s understanding that migration is really about translating meaning, not just code. It’s about preserving the institutional theories that made your systems reliable, not just making them run on modern infrastructure.Once you see the fourth dimension, everything else makes sense. The projects that succeed aren’t just about moving code—they’re about preserving an essential competitive advantage. Many of the ones that fail are undermined by the accidental loss of decades of accumulated wisdom.

The question isn’t whether to modernize your mainframe systems; the question is how to do it effectively and in a way that preserves their intelligence.

Next Article in this Series

-

March 12th, 2025

Leadership Excellence. Cloud Migration Visionary.

Heirloom Computing—recognized as a pioneer for IBM Mainframe Modernization.

“Heirloom is setting new standards in cloud migration, earning Gary the prestigious title of Cloud Migration CEO of the Year 2024.”

-

March 12th, 2025

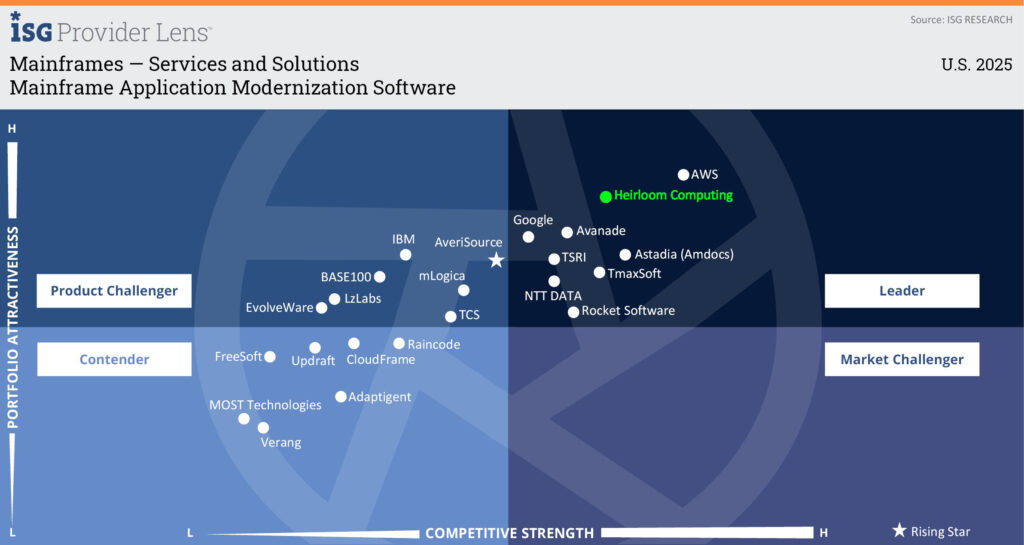

Heirloom Computing Named a Leader in the ISG Provider Lens™ Mainframe Services & Solutions U.S. 2025 Quadrant Report

Heirloom® recognized as Leader for Mainframe Application Modernization Software.

Information Services Group (ISG), a well-known technology research and advisory firm renowned for its industry and technology expertise, has named Heirloom Computing a Leader in its Mainframe Services & Solutions U.S. 2025 Quadrant Report.

“Heirloom Computing’s toolset offers rapid transformations with precise results. It has added GenAI capabilities to enhance speed and quality, delivering clean Java code that is easy to improve and maintain.” – Pedro L. Bicudo Maschio, Distinguished Analyst and Executive Advisor, ISG

Companies that receive the Leader award have a comprehensive product and service offering, a strong market presence, and an established competitive position. The product portfolios and competitive strategies of Leaders are strongly positioned to win business in the markets covered by the study. The Leaders also represent innovative strength and competitive stability.

Enterprises with IBM mainframes are increasingly looking to modernize their mainframe ecosystem. Increasing costs, decreasing skills, and a need to make application workloads more agile are driving the modernization wave. Heirloom migrates mainframe workloads using compiler-based refactoring to produce cloud-native applications that run on any platform.

Highlights from the report:

“Heirloom Computing offers a differentiated replatforming and refactoring technology renowned for its rapid processing of large code bases. It generates native Java applications that run on any cloud, enabling clients to retain source code in COBOL/PL1 or Java.”

-

February 3rd, 2025

Heirloom Computing Named as the IBM Mainframe Migration Solution Company of the Year by CIOReview

Heirloom® h/GENAI™ — Transforming Mainframes for a Future-Ready World.

“We put the reins [of IBM Mainframe Modernization] in the hands of our customers.” – Becky Etheridge, Chief Partner Officer

-

April 4th, 2024

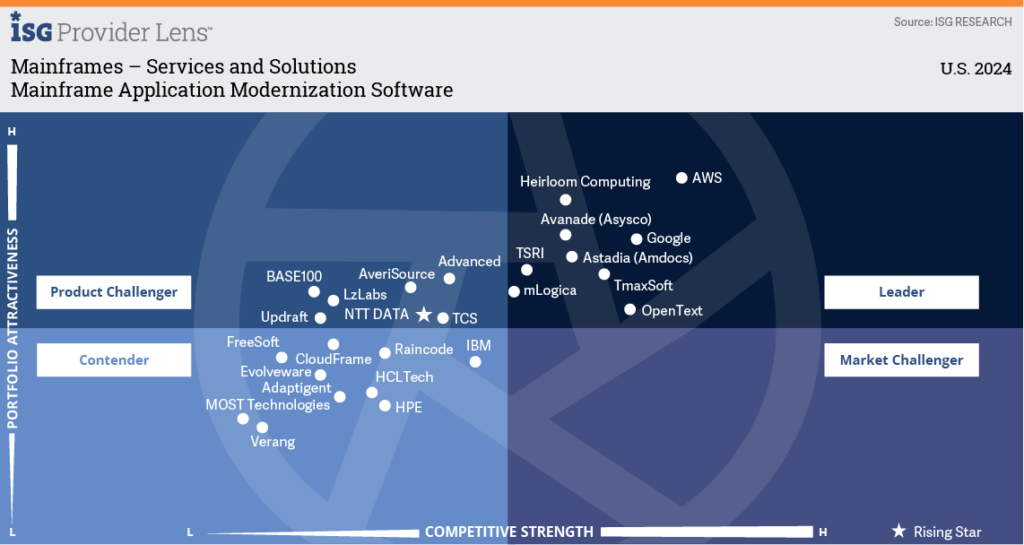

Heirloom Computing Named a Leader in the ISG Provider Lens™ Mainframe Services & Solutions U.S. 2024 Quadrant Report

Heirloom® recognized as Leader for Mainframe Application Modernization Software.

Information Services Group (ISG), a well-known technology research and advisory firm renowned for its industry and technology expertise, has named Heirloom Computing a Leader in its Mainframe Services & Solutions U.S. 2024 Quadrant Report.

“Heirloom has rapidly gained market share by offering a fast modernization option to handle large applications. It offers the flexibility to choose between replatforming or refactoring applications, offering clients greater control over their modernization journey.” – Pedro L. Bicudo Maschio, Distinguished Analyst and Executive Advisor, ISG

Companies that receive the Leader award have a comprehensive product and service offering, a strong market presence, and an established competitive position. The product portfolios and competitive strategies of Leaders are strongly positioned to win business in the markets covered by the study. The Leaders also represent innovative strength and competitive stability.

Enterprises with IBM mainframes are increasingly looking to modernize their mainframe ecosystem. Increasing costs, decreasing skills, and a need to make application workloads more agile are driving the modernization wave. Heirloom migrates mainframe workloads using compiler-based refactoring to produce cloud-native applications that run on any platform.

Highlights from the report:

“Heirloom Computing offers a differentiated replatforming and refactoring technology renowned for its rapid processing of large code bases. It generates native Java applications that run on any cloud, enabling clients to retain source code in COBOL/PL1 or Java.”